Recalling an Era When the Color of Your Skin Meant You Paid to Vote

Celebrating the 50th anniversary of a ruling that made the poll tax unconstitutional

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/2a/ae/2aae5f93-d68f-4f3e-93cc-78dec0043224/2012_104_001-web-resize.jpg)

In January 1955 in Hardin County, Texas, Leo Carr had to pay $1.50 to vote. That receipt for Carr's "poll tax" now resides in the collections of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture. In today’s dollars, Carr paid roughly $13.

“It’s a day’s wages,” explains William Pretzer, the museum’s senior history curator. “You’re asking someone to pay a day’s wages in order to be able to vote.”

Pretzer says the museum accepted the donation of the receipt from Carr’s family in 2012 as a vivid and a significant example of the way that voting rights were denied to African Americans. Poll taxes, quite simply a tax to pay to vote, were enacted in the post-reconstruction era from the late 19th to the very early 20th century. But they remained in effect until the 1960s.

This month marks the 50th anniversary of the Supreme Court’s Harper v. Virginia State Board of Elections decision to strike down poll taxes. And as voters head to the polls for the upcoming 2016 presidential elections, some, including former U.S. Attorney Eric Holder, have suggested that voting rights are once again under siege.

“After the 1870s, particularly in the southern states, there was an effort to restrict any kind of political power for African Americans,” Pretzer says. In the immediate post-Civil-War era, when voting rights were accorded to African Americans in the south, thousands registered, voted and ran for office. “There was great concern on the part of the white power structure that this was a revolution in their lives.”

Southern legislators began to find ways of limiting African-American rights, and one of the major ways was to enact barriers to prevent them from voting. A series of laws were passed state by state in the south, ranging from literacy tests to poll taxes. This was an effort to keep blacks as far out of politics as possible without violating the 15th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which prohibited governments in the nation from denying a citizen the right to vote based on that citizen’s “race, color or previous condition of servitude.”

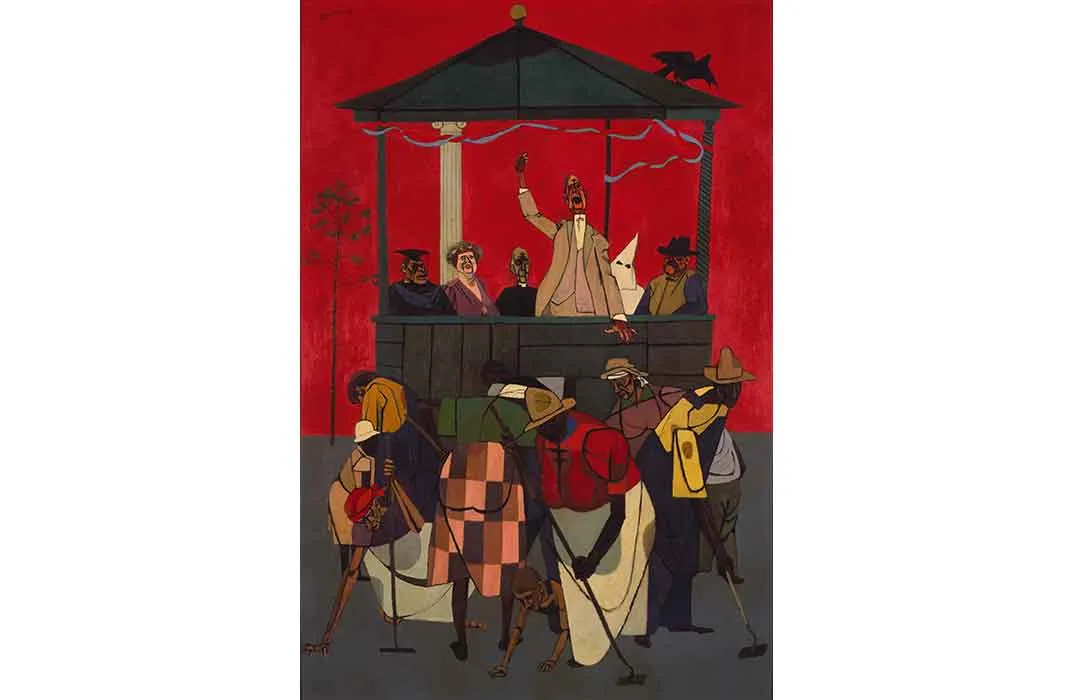

By 1902, all 11 of the former Confederate states had enacted a poll tax, along with other measures including comprehension tests, voter intimidation and worse.

“When people went to register to vote, their names would become known in the local community,” Pretzer says. “What you see is everything from simple harassment—people being insulted, pushed, shoved or harassed on the street—to being murdered.”

Poll taxes survived a 1937 U.S. Supreme Court challenge in the case Breedlove v. Suttles, which upheld a Georgia poll tax on the grounds that voting rights are conferred by the states, and that the states may determine voter eligibility as they see fit, save for conflicts with the 15th Amendment concerning race, and the 19th Amendment concerning sex.

But during the tumultuous battles of the civil rights movements, particularly following the landmark Brown v. Board of Education decision in 1954, activists saw poll taxes and similar policies as barriers to the voting rights of African Americans and the poor.

In 1962, the 24th Amendment was proposed, prohibiting the right to vote in federal elections from being contingent on the payment of a poll tax. It was ratified in 1964. But five states still retained the use of poll taxes for local elections.

Two years later, on March 24, 1966, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Harper v. Virginia Board of Elections, that poll taxes for any level of election were unconstitutional.

Lena Carr says she donated the 1955 Texas poll tax receipt from her uncle, Leo, partly because of her surprise that her family had been involved in the battle for voting rights in the Civil Rights era. The family found the receipt in a suitcase, after Leo’s mother passed away. When they went through it, there it was, nestled among old family pictures.

“I really was surprised, because my uncle never really talked a lot about voting,” says Carr, 54, who now lives in Kansas City, Missouri. “It shocked me that he actually went out and participated and paid. . . . In that era, I didn’t really know my family actually did any of that until I opened up that suitcase.”

Carr says the other reason she chose to donate this piece of her family’s history is because she thought it would be useful and inspiring.

“A lot of the young people don’t realize the things people had to go through to vote,” Carr says thoughtfully. “I thought they would recognize and realize what people did before them, how far they came, and what they got from that generation.”

Carr says that she is concerned about the voting restrictions that are being enacted in states ranging from Texas to Virginia to Wisconsin.

“I feel like history repeats itself, and if people don’t start to become aware of what’s happening in the world and take stock, we’ll be back at that point,” Carr says.

In 2012, then-U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder blasted Texas over its voter ID law, saying “we call those poll taxes,” adding that many of those without IDs “would have to travel great distances to get them, and some would struggle to pay for the documents they might need to obtain them.”

Smithsonian curator Bill Pretzer sees similarities.

“You have to have a particular kind of ID,” he explains. That includes identification offered through the state or federal government, military IDs, a state handgun license, a U.S. citizenship certificate, or a U.S. passport.

“The kinds of documentation that’s needed for this voter ID cost money,” Pretzer says. “An individual who doesn’t have their own transportation, or would need to take time off on an hourly basis … is going to suffer economically.”

The Department of Justice is in ongoing litigation related to voter ID laws in both Texas and North Carolina, saying both states laws would “have the result of denying or abridging the right to vote on account of race, color, or membership in a language minority group.”

Texas was allowed to enforce its law during the 2014 elections and also during its primary this month.

Last August, a three-judge panel of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit ruled that the Texas law discriminated against African-American and Latino voters. But it also said that a district court must re-examine its conclusion that Texas acted with discriminatory purpose, and that the lower court should seek ways to change the voter law without overturning it entirely.

At the time, Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton issued a statement saying the intent of the law “is to protect the voting process in Texas,” and noting that the U.S. Court of appeals had rejected the claim that the law was a poll tax. This month, the full 15-member Fifth Circuit voted to hear the case again. Paxton called the decision “a strong step forward in (Texas’) efforts to defend the state’s voter ID laws.”

“There are some very standard issues from time immemorial, about power, about control, about hierarchy, about opportunity, about equality, that people struggle over,” Pretzer says.

The Carr family poll tax receipt will likely go on view in the new museum (which opens on September 24, 2016) some time in 2018 and until then will become available online. Pretzer says such artifacts are important because they make real something that is hard to imagine.

At the BET Honors in Washington, D.C., this month, former U.S. Attorney General Holder issued a call to arms to people who are considering not voting in this current election season.

“There is absolutely no excuse not to vote,” Holder said. “People fought and died for the right to vote. It is an obligation of every American. … Otherwise, you are doing a disservice to the people who shed blood.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/allison.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/allison.png)