In Japan, Autumn Means a Parade of (Not-at-All-Creepy) Robot Puppets

A 350-year-old festival in Takayama celebrates creativity — and contains the seeds of modern robotics

Twice a year, the village of Takayama in the Japanese Alps parades its treasures through town: 23 carved wooden floats covered in gold and lacquer. These ornate yatai date back more than 350 years to Japan’s surreal, culturally rich Edo period, when the nation was closed to the outside world. In isolation, Japanese artists flexed their creativity — and fabricated a few high-tech surprises, too.

Woodworkers, silk merchants, and other skilled artisans populated 17th-century Takayama. Since Samurai rulers forbade the business class from flaunting its wealth, affluent merchants poured their resources into elaborate religious ceremonies instead. The mountain town’s twice-annual harvest festivals offered an outlet for creative competition between various districts. Merchants hired skilled craftsmen to build and decorate yatai more magnificent than those of their neighbors.

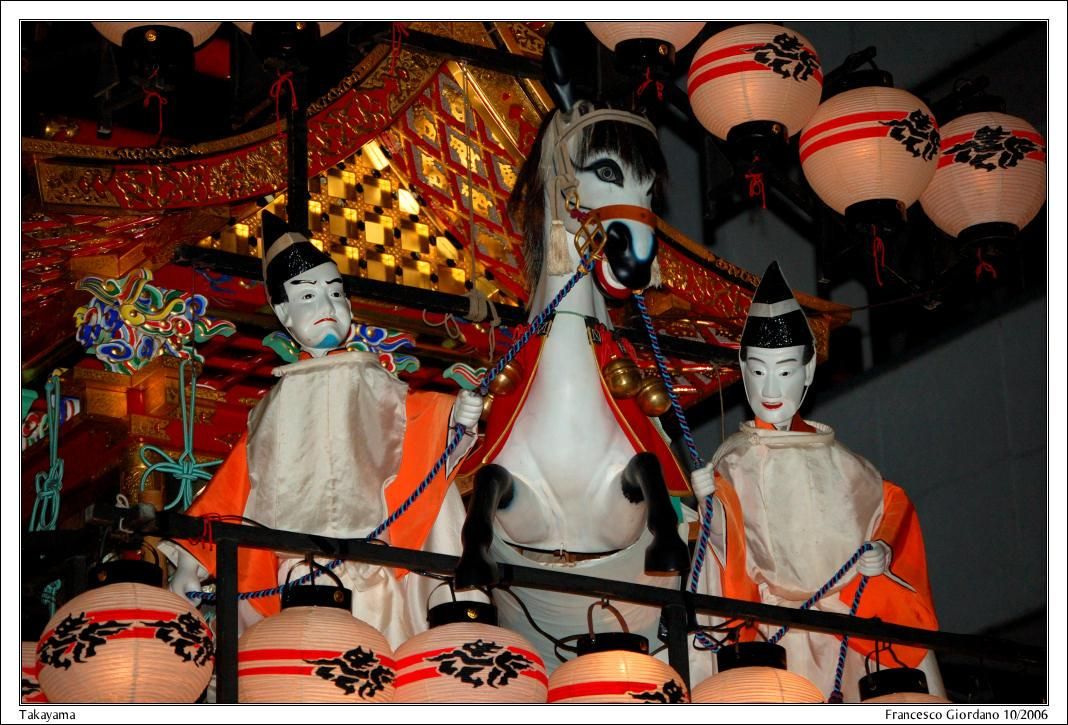

The result? Opulent carriages embellished with gilded animals, silk brocade, and shiny red and black lacquer. Several stories tall, the dazzling wheeled floats weighed so much that heaving one through town required 20 men.

Three-hundred-and-fifty years later, Takayama residents still dress in costume and pull the yatai through the town’s narrow streets at harvest time. Hypnotic flute and drum music transports participants back in time. As the procession travels across Takayama’s glossy red bridges, the carriages’ vibrant colors reflect in the streams below. Nighttime processions are even more magical. At twilight, hundreds of glowing paper lanterns add shine to the carved floats’ lacquer and gold accents.

Each yatai has a unique name and history. Golden phoenixes symbolizing eternal life rise from the top of one float, and delicate, carved peonies and chrysanthemums decorate the wheels of another. Kame Yatai sports a giant turtle with a weird, human-like head — apparently the father and son who carved it in the early 1800s had never seen a real turtle.

And there’s something else on board some of the floats: Japan’s prototype robots. Called karakuri ningyō, these mechanical dolls spring to life on the float’s raised stage. Hiding below, a team of nine puppeteers manipulates each doll by gently tugging on invisible strings.

“Karakuri” refers to a mechanical device designed to trick, tease or inspire wonder. It relies on the element of mystery and surprise. “Ningyō” loosely translates as puppet, doll or effigy. While other marionettes are controlled by visible strings or wires, these ones are maneuvered by 36 baleen strings concealed in a wooden arm. Hidden springs and gears imbue the mechanical dolls with surprising, lifelike gestures. The puppets’ faces are carved and painted so that subtle head movements and the play of light and shadow will convey varied emotions — joy, fear, anger, sadness and surprise.

These proto-robots typically bring myths or legends to life, often reenacting a scene from a larger play. One of Takayama’s oldest floats, Hoteitai, features three beloved characters: Hotei, the pot-bellied god of good luck, and two impish children. During festival performances, the little boy and girl puppets swing like acrobats on trapeze bars to land, as if by magic, on Hotei’s shoulders. For the finale, Hotei’s fan shoots up to become a flagpole. A banner unfurls, bearing a message about the virtues of modesty.

As the first automata in Japan, karakuri played an important role in the rise of technology. During the Edo period’s enforced seclusion, Japanese scientists absorbed whatever western technology they could find and adapted it to their purposes. Their first experiments involved clocks and mechanized dolls. Japan’s early engineers employed the puppets to explore physics and automation.

A revered karakuri maker, Tanaka Hisashige, founded the precursor to Toshiba. Toyoda Sakichi fine-tuned the Toyota assembly line after working with mechanized dolls. And Kirsty Boyle, an authority on ancient Japanese puppets, says that walking karakuri inspired the invention of humanoid or biped robots.

Today’s puppeteers pass their knowledge on to younger family members. Tomiko Segi, curator of the Takayama Festival Floats Exhibition Hall on the grounds of the Sakurayama Hachiman shrine, tells Smithsonian.com that it can take decades to perfect the art of making these proto-robots move. “One of the performers started learning how to move the karakuri when he was nine years old,” she says. “Now he is 30.”

The fall festival, or Hachiman matsuri, starts October 9. But missing the festival itself doesn’t mean missing out. Wander around Takayama long enough and you’re bound to find its yatai gura. Scattered throughout Takayama, these narrow, thick-walled storehouses were built especially for the festival floats. Their 20-foot-tall doors give them away. For a glimpse of the floats themselves, check out the Takayama Festival Floats Exhibition Hall — it displays a rotating selection of four yatai year-round. Or catch a puppet performance at Shishi Kaikan a few blocks north of Miyagawa River to recapture that festival feeling all year long.