We Thought We’d Be Living in Space (or Under Giant Domes) By Now

An inflatable space habitat test highlights the futuristic visions we’ve had for housing, from cities under glass to EPCOT

:focal(1650x1272:1651x1273)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d0/a1/d0a1c212-9031-419e-9be5-3edf1882cf9b/bigelow_alpha_station.jpg)

The International Space Station is known for a distinct lack of personal space, with crews packed into phone booth-sized beds and assaulted by continuous light, sound and surveillance. But if things go right during an upcoming SpaceX resupply mission, currently scheduled for March 2016, the station could soon be a bit roomier and more relaxing.

After the Dragon capsule reaches the station, the ISS’s robot arm will pull out a device called the Bigelow Aerospace Expandable Activity Module, or BEAM—and the future of housing might just change forever.

The 13-foot-long module is being referred to by Bigelow Aerospace and NASA as an “expandable habitat,” but to the average viewer it will look more like a big white balloon. Think of it as a kind of spare room—one that cost NASA a cool $17.8 million. BEAM will arrive uninflated, but once it’s attached to one of the station’s nodes it will blow up, creating a new—if not entirely expansive—section of the ISS.

“I jokingly refer to it as a largish New York apartment,” says Mike Gold, director of D.C. operations and business growth for Bigelow Aerospace. BEAM isn’t intended to be used as living quarters, he notes. Rather, it will serve as a proof of concept for expandable habitats.

Gold sees another benefit to the module: a bit of peace and quiet. “Acoustically, it’s going to be the quietest location aboard the International Space Station,” he says. Will astronauts use it as a respite from the always-on environment of the bigger station? Right now, it’s unclear. In a release, NASA says only that the station will be measured and tested over time. But Gold thinks the module has the potential as a place for science experiments, stowage and other activities. After all, the concept has been tested before: In 2006 and 2007, the company launched the Genesis I and II missions, when expandable habitats headed into orbit via converted Russian ICBMs.

The limited plans for the habitat are a far cry from the “space hotel” label that has long been associated with the company. Bigelow Aerospace is owned by hotelier and real estate mogul Robert Bigelow, whose plans to take his empire to space have been the source of speculation and sometimes mockery since he launched the company in 1998.

That moniker irritates Gold, who calls it a “pernicious misconception.” He says that tourism is just a portion of the company’s long-term plan. The term has been in use since the module that inspired Bigelow Aerospace’s current projects, a NASA-designed inflatable crew quarters project known as TransHab.

TransHab turned out to be just a pipe dream—the project’s funding was cut in 2000 and it literally never left the ground. Bigelow snatched up NASA’s patent rights and used them to develop the technology.

If BEAM isn’t a space hotel, the company’s next project sure seems like one. Now that BEAM is ready to deploy, the company is perfecting the B330, an even larger expandable habitat that could be used for housing, research and development or astronaut training.

Unlike BEAM, the B330, named for its 330 cubic meters of internal space, is a completely independent module—it doesn’t need to hook up to the International Space Station, and it can support a crew of up to six. B330s can even be hooked up to one another to form free-floating commercial stations like Alpha Station, a proposed space station that Bigelow Aerospace claims could help nations develop their astronaut corps, perfect space travel and conduct research.

On its website, the company says it will offer things like one-off astronaut flights ($26.75 to $36.75 million per seat), leased space station space ($25 million for exclusive use of a schoolbus-sized space over a two-month period) and naming rights to Alpha Station ($25 million a year). Gold downplays the idea of space tourism, but doesn't discount it entirely. Perhaps it will be more lucrative—and realistic—once the company’s ambitious Olympus project, named for its godly 2,100 cubic meters of space, is complete.

There are still challenges to be addressed. Right now, the company relies on commercial resupply missions to the space station launched by companies like SpaceX to get its smaller modules into orbit. But commercial rockets are small, and many don't have enough power to launch the 20-ton B330. Bigelow notes that it designed that unit to fly on an Atlas V rocket, a dependable vehicle that has a launch capacity of just over 40,000 pounds. To get its more ambitious habitats off the ground, Bigelow Aerospace will probably need a rocket like NASA’s upcoming Space Launch System, or SLS, which will have an eventual lift capacity of 286,000 pounds.

Are expandable space stations (hotels or otherwise) the buildings of the future? Perhaps. Some people may ditch the idea of space tourism and become full-time space residents in structures like Bigelow's Olympus. Some may flee Earth due to overpopulation (there's an 80 percent probability that the world's population will grow to around 11 billion by the end of this century, and there are no signs of slowing).

And then there's the cool factor—some people may find that they simply prefer to live in microgravity surrounded by spectacular views of planets and stars all the time.

But commercial space projects are susceptible to funding issues, delays and development traffic jams, all of which could send the most optimistic predictions for the future of travel and housing tumbling back to Earth. And for every futuristic habitat success, there are scores of stalled or vastly altered projects. Here are a few of the other places we thought we’d be living by now:

In a Frank Lloyd Wright-Designed Utopia

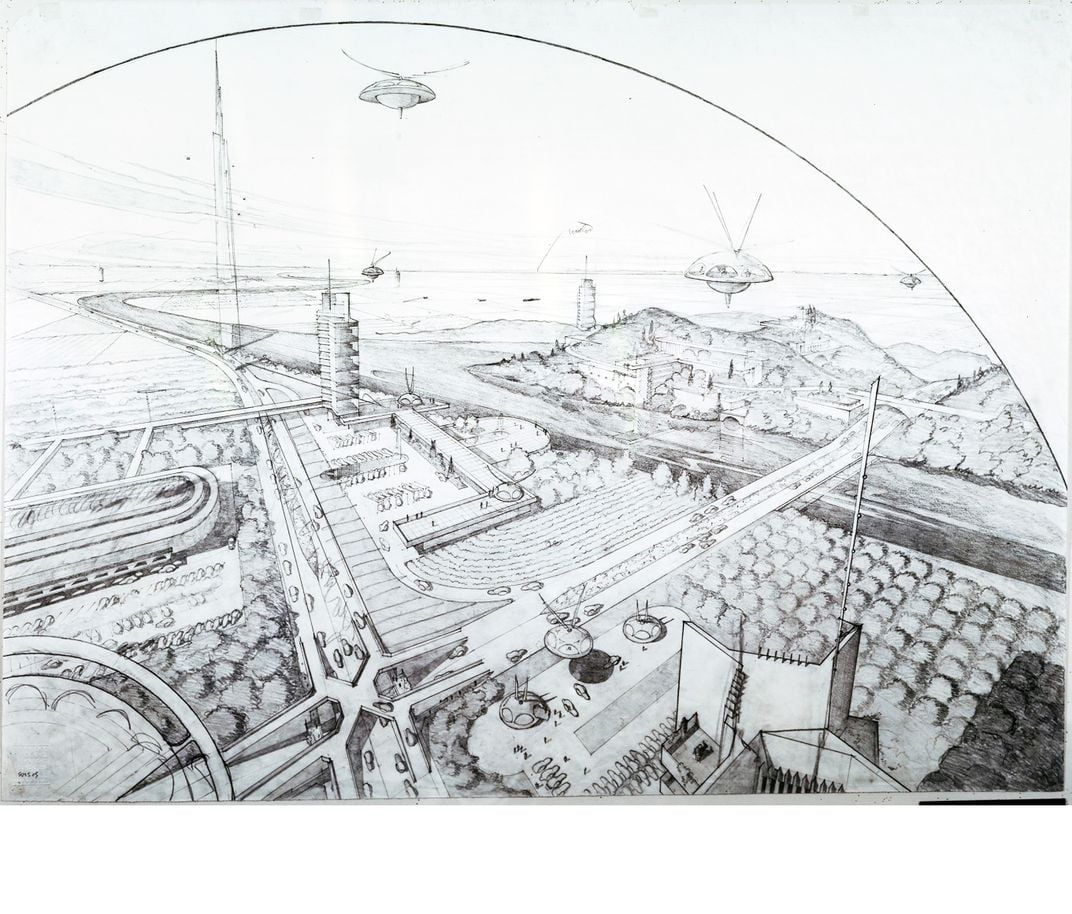

Frank Lloyd Wright didn’t just design gorgeous houses and museums—in the 1930s, he conceived of Broadacre City, a utopian alternative to the hustle and bustle of the typical metropolis. Wright was so enchanted by his idea of giving one acre to each family and ensconcing them in a sprawling suburbia without social problems or skyscrapers that he promoted it until his death in the late 1950s.

Beneath Lots and Lots of Glass

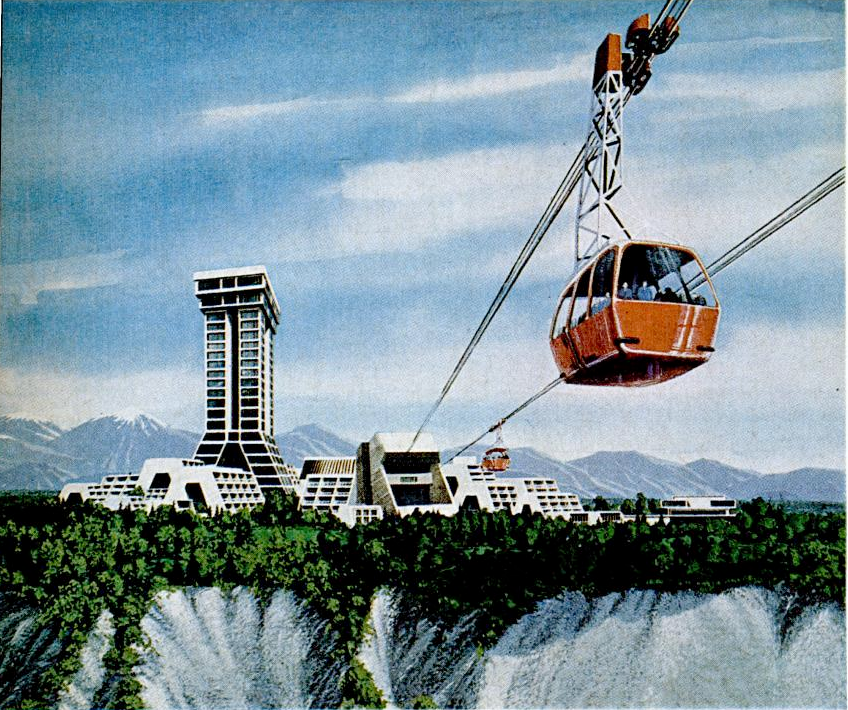

Does the thought of a trapped city full of monorails and monoliths make you think of Logan’s Run? The movie could well have been inspired by Seward’s Success, a metropolis planned in Anchorage, Alaska during the 1960s. The glass-covered city was designed for 40,000 residents complete with monorails and aerial trams—no cars allowed. Alas, Seward’s Success was never to be: The project was delayed and eventually canceled.

In Walt Disney World

Walt Disney wasn’t content as a groundbreaking animator and amusement park impresario—he wanted to change the face of U.S. cities, too. In the 1960s, Disney hatched an idea called “Project X” and began acquiring hundreds of thousands of acres of land in Orlando, Florida. The city would feature homes of the future designed by American corporations along a gigantic urban corridor. Eventually, the project was renamed E.P.C.O.T.—Experimental Prototype Community of Tomorrow—but it was downgraded to a section of Disney World after Disney’s death in the late 1960s.

In a Domed City in Minnesota

Few future cities came as close to fruition as the Minnesota Experimental City, or MXC. In 1969, Minnesota’s state legislature approved the formation of a steering committee to figure out new ways to solve problems of urban sprawl and quality of life. A 75,000-acre site was chosen and plans made to develop the community of Swatara into an environmentally friendly, car-free city with a gigantic geodesic dome. But legislators balked in the 1970s, and today Swatara is more ghost town than modern metropolis.

In a Carbon-Neutral Megalopolis

There are planned cities, and then there are planned cities. Dongtan, near Shanghai, was to be one such city—a gigantic “eco-city” designed to house 500,000 residents over the course of just 30 years. Dongtan was to house everything from a wind farm to power plants run by rice husks. All housing was to be built within a seven-minute walk from public transportation. But the carbon-neutral paradise never happened: Despite predictions that by 2050, the city would be as large as Manhattan, the project is now over a decade behind schedule.

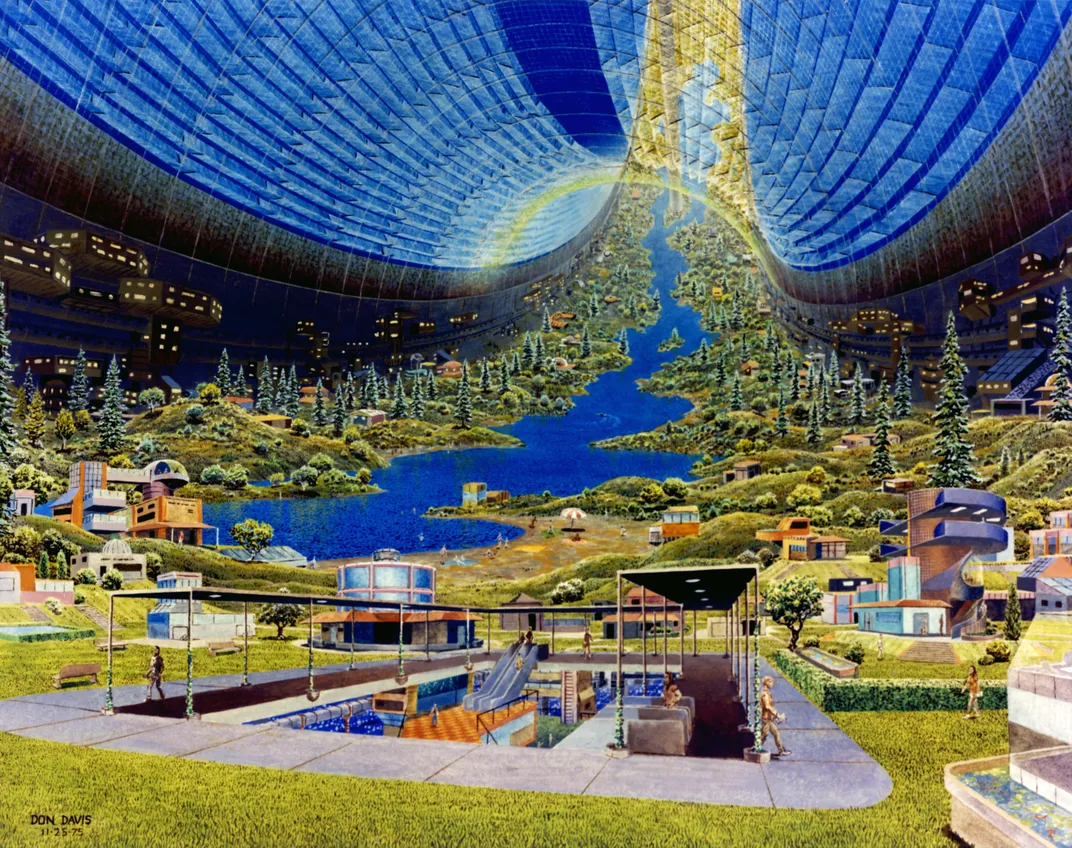

In the Ultimate Space Colony

In the 1970s, NASA’s Ames Research Center conducted a series of studies on the feasibility of colonizing space. The “summer studies,” as they came to be called, looked at whether space colonization was technically feasible. The answer was yes—as long as humans lived in spheres, cylinders or doughnuts complete with artificial gravity, plenty of greenery and shopping malls galore. One study acknowledged that though it might feel weird for people to live in such different environments, the effects could be mitigated by things like providing large vistas “to make the habitat large enough to lessen the sense of its being manmade.” Of course, the settlements never came to be—but who’s to say that NASA won’t one day brush off its old space colony suggestions?

Editor's Note: This story has been updated to better reflect the current launch capabilities for Bigelow's space habitats.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/erin.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/erin.png)